|

| Acts Passed at a Congress ... New York, 1789/90. |

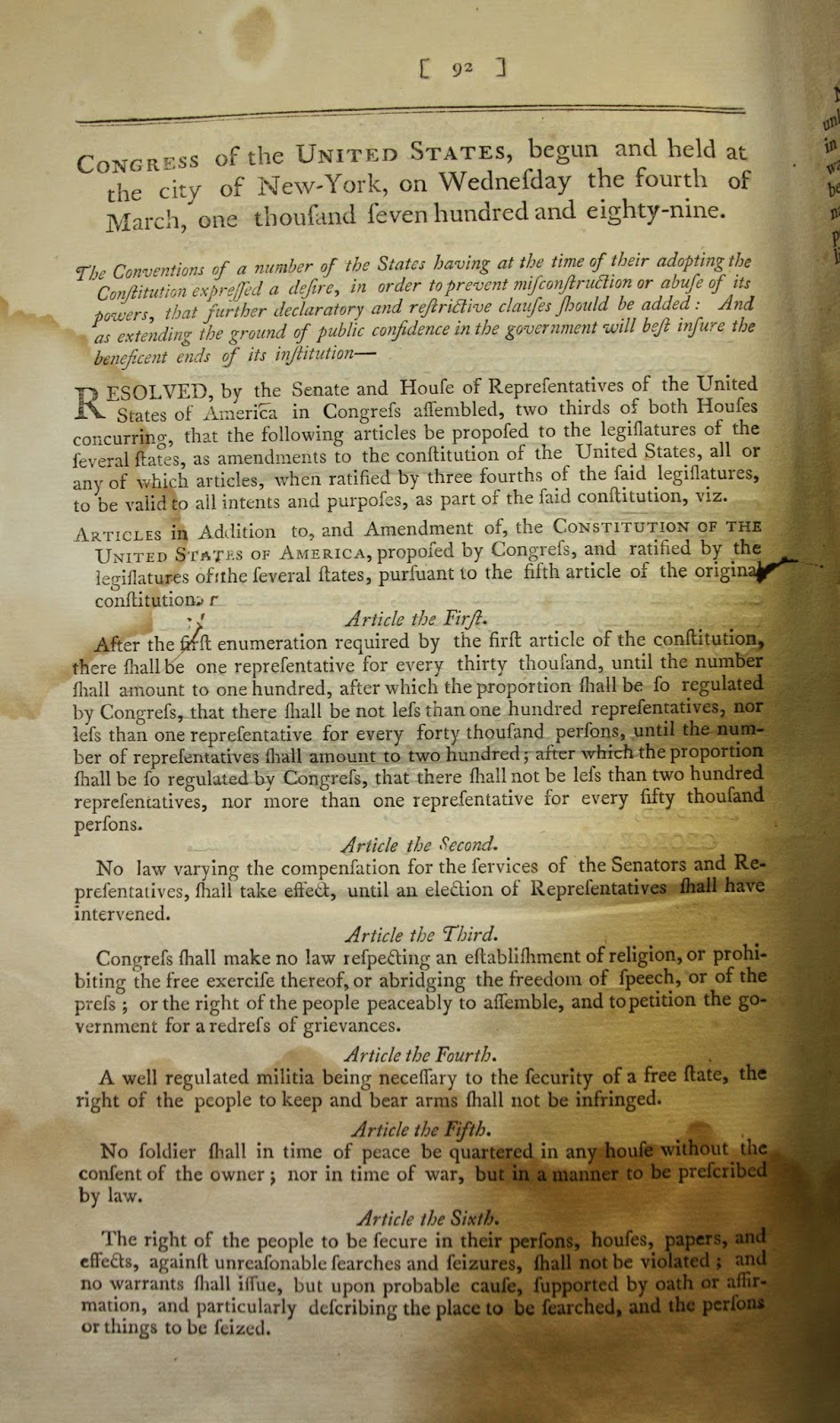

Our copy of these extraordinary session laws includes the original twelve amendments, after congressional passage but before ratification by the states. The now neglected "Article the First," concerning proportional representation, sits near the head of the page, and "Article the Second," on congressional compensation, follows it. Unratified at the time, "Article the Second" finally entered the constitutional canon in 1992, as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment. Particularly important for our upcoming exhibit is the Fifth Amendment, which began its life here as the Seventh. This great Amendment has Magna Carta in its direct lineage, as it includes the famous prohibition on the loss of life, liberty or property without due process of law. The Fifth Amendment (and its later partner, the Fourteenth) are still among the most important, and most discussed, amendments in US constitutional law.

Although there were a few earlier printings of early forms of the US Bill of Rights (notably the Gazette of the United States and New York Daily Advertiser carried Madison's original nine proposals in June 1789), our copy of the twelve amendments is quite special and rare, and also interesting for signatures and marks that add to its historical value. One, written at the end of the proposed amendments, toward the bottom of the now dampstained page, is the name "Muhlenberg." Above the signature is the printed name of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Frederick A. Muhlenberg, an interesting figure from Pennsylvania. The signature bears some similarities to an authentic autograph preserved online by the University of Pennsylvania. Another signature - that of a Jacob Frost of New York - can be found as well, along with the smaller, neater signature of William Frost. Perhaps Jacob was a son, or at least younger, since his unruly signature and marks look like practice writing.

Does our copy bear the signature of Frederick Muhlenberg, and if so, was he an owner or for some reason simply signed the copy? And who was the Frost family, who seemed to own this copy already in 1789 or 90, and perhaps left it "in the care" of a New York attorney, written as "___iel Sewall" on the back cover? What did this book mean to them, how did they come by it, and how did they use it? The answers would require a researcher's attention, but they are exciting and challenging. They are also just a few of the questions that can come up when looking at historical books - whether extraordinary or more mundane - with an eye to their particular histories!

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.