|

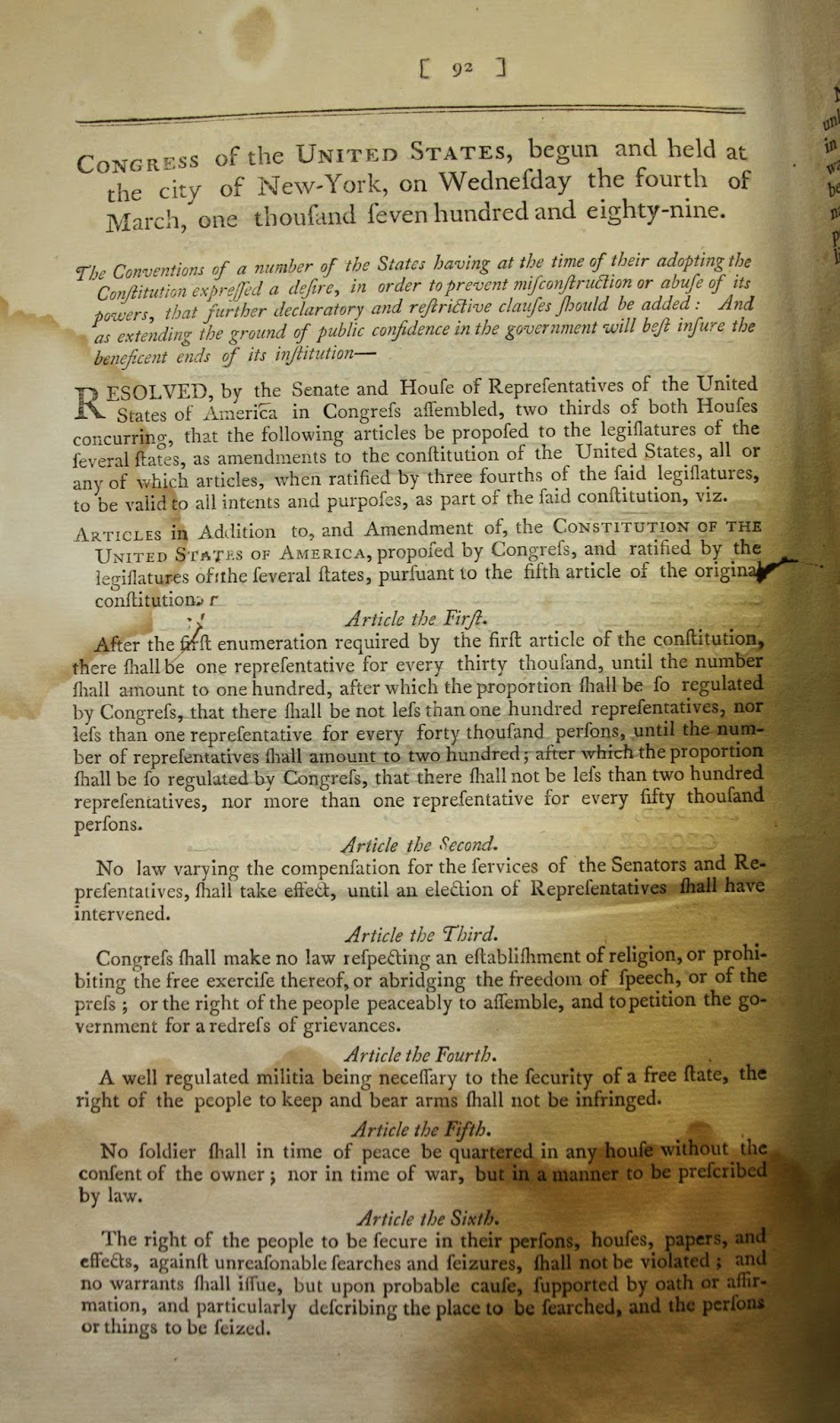

| Magna carta cum aliis antiquis statutis, London, 1540. |

Come join us in the Library lobby next Tuesday, February 3rd, to kick off the anniversary of Magna Carta! To start the 800th anniversary celebration there will be donuts, cookies, granola bars, chips, coffee and (English) tea, starting from 10am and until we run out.

We'll also have two contests for multiple prizes, ranging from Amazon gift cards to food and drink at Republic. Don't forget to pick up some Magna Carta swag as well.

Last but not least, see a historic Magna Carta from the Library's rare book collection.

Next month, at the end of February, a new exhibit will open in the Riesenfeld Center, devoted to the history and reception of Magna Carta. "Magna Carta, 800 Years: Rights and the Rule of Law," will highlight the rich legacy of Magna Carta in England and America, as seen through the Riesenfeld Center's rare books collection. Stay tuned here for more...

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections