1. How many accounts, published in 1850, do we have in the rare books collection related to the notorious Webster-Parkman murder case? (search library 'catalog only,' and scope 'law library rare books')

News from the Stefan A. Riesenfeld Rare Books Research Center at the University of Minnesota Law Library

Pages

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Halloween Rare Books Quiz!

1. How many accounts, published in 1850, do we have in the rare books collection related to the notorious Webster-Parkman murder case? (search library 'catalog only,' and scope 'law library rare books')

Monday, October 19, 2020

Two New Library Digital Exhibits: Treasures of the Riesenfeld Rare Books Center

The Law Library and Riesenfeld Center are pleased to announce two new digital exhibits:

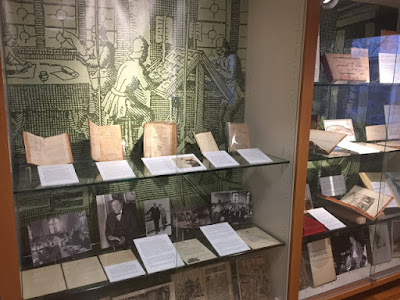

"Noted and Notable: Treasures of the Riesenfeld Rare Books Research Center"

and

The digital exhibits preserve and make available online the Riesenfeld Center's spring exhibits, highlighting treasures of the Law Library's special collections. In particular, the items in these exhibits have been chosen for their unusual value as artifacts, including such features as interesting annotations, associations with notable former owners, striking illustrations, beautiful bindings, and other properties that make historical law books fascinating objects that are worthy of study.

"Böcker Har Sina Öden' (Books Have Their Destinies)," was curated by Professor Eric Bylander, who has been twice a visiting professor at the Law School and is Distinguished University Professor at the Faculty of Law, Uppsala University. "Noted and Notable: Treasures of the Riesenfeld Rare Books Research Center" is still open by appointment for viewing in the Riesenfeld Center.

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections

Tuesday, October 13, 2020

New Law Library Digital Exhibit: "Law and the Struggle for Racial Justice"

The Law Library and Riesenfeld Center are pleased to announce a new digital exhibit:

The digital exhibit preserves online the Riesenfeld Center's new fall exhibit, which aims to continue a number of important and ongoing conversations at the Law School regarding race and the law. In particular, the exhibit draws on the extensive collections at the Riesenfeld Center to highlight important moments in the Black American struggle for racial justice, from the 19th and 20th centuries. The exhibit considers historical legal cases, legislation, and events that saw civil rights denied, limited, and advanced, from early anti-slavery movements, to the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 60s, and projects for police reform in the 1980s.

Wednesday, September 9, 2020

New Library Exhibit: "Law and the Struggle for Racial Justice"

"Law and the Struggle for Racial Justice: Selected Materials from the Riesenfeld Rare Books Center"

Despite founding ideals of freedom and common civil rights, the United States has a long history of systemic racial disenfranchisement. Many forms of exclusion and control based on race have been enforced by American law, deeply affecting the lived experience of minority communities. The unequal treatment of diverse racial and ethnic populations endures today, continuing to challenge us to critically examine our practices and beliefs and to recommit ourselves to a more fair and equal society.

"Law and the Struggle for Racial Justice" highlights material in the Center's collections related in particular to the Black American struggle for equal rights, as seen in historical cases, legislation, and the evolving aims and achievements of civil rights movements. The exhibit calls attention to historical exclusion, to moments of progress, and to ongoing obstacles faced by communities of color as they have sought racial justice. It is hoped that historical perspectives will stimulate further reflection on the scope of these challenges and help us to envision a future in which rights are fully and equally protected for all.

The exhibit is open by appointment, and a digital version of the exhibit will be released this fall. For more on particular items in the exhibit, see several recent blog posts (here and here). For more information, please contact Ryan Greenwood (rgreenwo@umn.edu; 612-625-7323).

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections

Wednesday, August 26, 2020

Upcoming Exhibit: Commission on the Harlem Riot, 1935

The Harlem riot of 1935 has been called by several scholars the first modern race riot. A Black Puerto Rican youth, Lino Rivera, was apprehended by a Harlem, New York, shop employee for stealing a penknife. The boy bit the employee but was later released by police. A false rumor that Rivera had been beaten to death in the shop led to a riot the same night, during which more than one hundred were injured and arrested, and three African Americans were killed. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia set up a biracial commission of noted figures to investigate the causes of the riot, likely at the recommendation of Walter White, then secretary of the NAACP.

The commission included Eunice Hunton Carter, the first African-American woman prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney's office; Morris Ernst, co-general counsel of the ACLU; A. Philip Randolph, the prominent labor and civil rights leader; and Countee Cullen, the poet and novelist, among others.

The commission set up several subcommittees, tasked with reports in areas including Crime and Police, Housing, Education and Employment Discrimination. More than 150 witnesses testified at a series of public and private hearings before the commission.

Published a year later, the resulting report was more than 100 pages. It outlined the events of March 19th that led to the riot and recommended reforms by the City government in Harlem in relation to housing, health care, education and policing.

The subcommittee report displayed in the upcoming exhibit is a separate typescript addressed to Mayor LaGuardia by Arthur Garfield Hays, a noted lawyer and the subcommittee chair. One other copy of the report is recorded, held at the New York Public Library. The report discusses the events of the riot and subsequent incidents involving police. Just as the overall report acknowledged the professionalism of many officers involved in the events, the subcommittee report thanks the police chief and several officers for cooperating with the investigative commission.

Nevertheless, the report addresses the incidence of police brutality during and after the riot, citing particular officers for avoidable and unnecessary deaths and other instances of violent misconduct. Among remedies, the subcommittee recommends that police be better trained on the limits of their authority to use force and on due process rights; that rapport with the community should be fostered rather than antagonism; and that greater accountability was necessary. Regarding the last, the report recommends the creation of a biracial committee in Harlem to receive and evaluate complaints of police misconduct, then to report them directly to the office of the Commissioner of Police. The subcommittee advises that resulting criminal misconduct cases be punished not only internally but turned over to the District Attorney's Office for prosecution. The report concludes by arguing, as the general report would examine in greater detail, that in Harlem the wider social inequalities faced by the Black community in relation to housing and rent, employment and schools also had to be addressed in order to restore social order.

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections

Thursday, July 2, 2020

Upcoming Fall Exhibit: Racial Justice and the Law

The Center's rare book collection holds an important set of titles related to 19th-century anti-slavery movements, and to civil rights movements in the late 19th and 20th centuries. As leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois remarked in the early 20th century, while Reconstruction had real but limited effects, civil rights movements suffered a grave setback with the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

At the same time, organizations dedicated to the achievement of equal civil rights emerged. The Afro-American League, led by Timothy Thomas Fortune, and the Afro-American Council - the latter of which held its annual meeting in 1902 in St. Paul - were eventually succeeded by the NAACP, founded in 1909 by W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Mary White Ovington, and Moorfield Storey, among others. These and other organizations arose in response to segregation enforced by law, and lawless violence, including lynching, faced by African Americans. In the late 19th century, many states passed segregationist Jim Crow laws, and with the moral blindness of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) segregation was ruled a constitutionally-protected principle.

The NAACP initiated lawsuits targeting segregation and discriminatory laws, and made progress in some cases. It pursued anti-lynching laws, and lawsuits following race riots, which eventually resulted in some expansion of federal jurisdiction over states' criminal justice systems. A prominent case with strong NAACP support was that of Dr. Ossian Sweet, which features in our collection and reflects on the history of segregation in America. The following description is based on the excellent, detailed account of the Sweet trials by Mike Hannon for our Clarence Darrow Digital Collection.

In 1925, Dr. Sweet, an African American medical doctor, moved with his family into a segregated white neighborhood in Detroit. Throughout America, segregation was maintained informally and formally. Often racial covenants prevented African Americans from owning houses in white neighborhoods (the practice flourished in Minneapolis, for example). The 1920s were a time of nation-leading demographic growth in Detroit, which saw an influx of African American and white workers looking for jobs and housing. The Ku Klux Klan also had a presence in the city and local political clout. In the case of Sweet, as in other cases, white neighbors resorted to tactics of intimidation and violence to drive African Americans from their homes.

In September 1925, just after moving into a house on Garland Street, the Sweet family faced a mob massing outside their home. Family members and friends were called to help while the crowd began to hit the house with rocks and yelled epithets. Shots rang out from the house and struck two people, one of whom was killed. In the subsequent trials of Dr. Sweet, his family and friends, only Henry Sweet, Ossian's brother, would admit firing into the crowd.

The defense of Sweet, his family and friends was organized by the NAACP, which recruited the services of the nationally-renowned trial lawyer, Clarence Darrow. (Darrow's storied career is preserved in our library, which holds the largest collection of his letters, and material from his life and cases. Darrow was friends with founders of the NAACP and served as a member of its general committee.) At the first trial, for murder and conspiracy, Darrow and the defense team consistently argued that the Sweet family acted in self-defense while in direct fear of their lives.

One aspect of Darrow's argument was that the 'reasonable man' standard, applied to gauge the fear of the defendants, had to be that of a black man in a similar situation of violence and threatened violence. The arguments at the first trial were bolstered by the testimony of several other African Americans, who had been chased from their Detroit homes by fear of violence and threats; and others who testified that between 400 and 500 people were present outside the Sweet home on the fateful day.

In a long closing argument, Darrow argued that suffering due to race and deep inequality were at the heart of the case, appealing to a white jury to see past their own racial prejudice. In his jury instructions, Judge Frank Murphy noted that a black man's home was his castle in the same way as that of a white man: there was no right to invade or assail it (familiar as the 'castle doctrine,' with its long provenance). The jury deliberated for 46 hours and came back deadlocked; the judge declared a mistrial.

|

| Jury in the Henry Sweet trial |

The prosecution vigorously pursued a retrial, and Darrow filed for the defendants to be tried separately. The first tried was Henry Sweet. The trial followed similar lines of argument; Darrow now had more success in hounding prosecution witnesses. In part, he pressed for admissions that a neighborhood homeowners association was organized to keep African American owners away and would use violence to do so. During the closing argument, attended by hundreds inside a packed courthouse, Darrow asked the all-white jurors again to set their prejudices aside and put themselves in the shoes of the Sweet family. He attacked the prosecution's case for eight hours, asking jurors to understand the defendant's plight and the history behind it. After jury instructions of more than two hours, the jury came back with a verdict of not guilty in three hours; no further cases were tried.

The case was a notable victory for the family, the NAACP and Darrow, and reflected on issues of race and justice in 1925 that are still with us today. Racial covenants were not struck down until 1948, and de facto segregated communities have left their legacy across urban and suburban American landscapes. Self-defense doctrines have come back into the spotlight more recently in broader debates over lethal force used by police and private citizens, particularly when victims are minorities. In all of these, the problems of racial injustice that we still struggle with, and must continue to struggle with for a more equitable future, have come directly back to the foreground.

- Ryan Greenwood, Curator of Rare Books and Special Collections

Monday, June 8, 2020

Announcement: Morris L. Cohen Student Essay Competition

© Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Equal opportunity educator and employer.